About the artist

A thing is space beyond

which there is no thing

Joseph Brodsky, Still Life

Sculpture would be the embodiment of places.

Places, in preserving and opening a region,

hold something free gathered around them which

grants the tarrying of things under consideration

and a dwelling for man in the midst of things.

M. Heidegger, Art and Space

In Jewish religious schools, when a child starts learning how to read, he is given a lick of honey smeared on the alphabet. This forms a special sensory memory that preserves emotions and feelings. Julia Segal has never attended a Jewish school. Her gift of rememberance

through feelings is innate. Such kind of memory is extremely active — the slightest impulse, touch, smell, taste, or even a mere glance at a random object can be enough to stir up a storm of memories. These remembrances are of moods, of emotional upheavals and of inner experiences that are more copious in human life than memories of concrete dates and events. To transmit, articulate, or simply to retell

these experiences is extremely hard. It requires the novel’s bredth and scale, the multi-dimensionality of film, or the totality of an art installation. Julia Segal has achieved this expression through the limited set of tools that figurative sculpture provides: material, form, volume, and narrative.

Segal’s works are, for the most part, monochrome: the gray of the concrete, of rain gutters and of old asphalt. This produces an almost tactile sensation of an object emerging out of the wall’s surface. It is no coincidence that the artist’s favorite format is sculptural relief. Relief is unevenness, roughness, protuberance on the surface (no matter if the surface is horizontal or vertical). One can feel it with one’s hands. Segal’s sculptures are extremely tactile. Even the surface of her material is always uneven, as rough as a calloused hand or a brick wall. This amplifies the already enormous internal pressure that form imparts on the material surface. It’s as if the molecular bonds are about to break apart, releasing that pressure and leaving matter behind, like old skin. Sensing this tension, Segal begins to make cuts in her reliefs, cutting out windows and doors. One could say that she creates light inside them. The relief acquires volume, and with it a new space is born.

Thus come to life the recollected worlds of Julia Segal. They are always small-scale, as if we grew up, and they’ve stayed the same. That is why you can peek inside, take them with your hands, put them on the table. Every piece by Segal is a thing in itself, or more precisely, the Object. Jean Baudrillard wrote, “The object is that through which we mourn for ourselves, in the sense that, in so far as we truly possess it, the object stands for our own death, symbolically transcended... “ Julia Segal creates metonymic portraits. Objects instead of people — an old coat, a wheelchair, a child’s table. But her objects are not anthropomorphic (or, more precisely, they are anthropomorphic to the extent that that an old object repeats the figure of its owner).

Segal recreates in detail the real things, as if reclaiming them back from time itself. However, these objects are someone else’s. And if one’s own object allows for at least a symbolic transcendance of death, then someone else’s, on the contrary, painfully highlights

its presence. Thus the artist reveals the emptiness that is formed in space and time with the departure

of each person. And this emptiness resounds with a “voice of gentle silence*.”

Haim Sokol

which there is no thing

Joseph Brodsky, Still Life

Sculpture would be the embodiment of places.

Places, in preserving and opening a region,

hold something free gathered around them which

grants the tarrying of things under consideration

and a dwelling for man in the midst of things.

M. Heidegger, Art and Space

In Jewish religious schools, when a child starts learning how to read, he is given a lick of honey smeared on the alphabet. This forms a special sensory memory that preserves emotions and feelings. Julia Segal has never attended a Jewish school. Her gift of rememberance

through feelings is innate. Such kind of memory is extremely active — the slightest impulse, touch, smell, taste, or even a mere glance at a random object can be enough to stir up a storm of memories. These remembrances are of moods, of emotional upheavals and of inner experiences that are more copious in human life than memories of concrete dates and events. To transmit, articulate, or simply to retell

these experiences is extremely hard. It requires the novel’s bredth and scale, the multi-dimensionality of film, or the totality of an art installation. Julia Segal has achieved this expression through the limited set of tools that figurative sculpture provides: material, form, volume, and narrative.

Segal’s works are, for the most part, monochrome: the gray of the concrete, of rain gutters and of old asphalt. This produces an almost tactile sensation of an object emerging out of the wall’s surface. It is no coincidence that the artist’s favorite format is sculptural relief. Relief is unevenness, roughness, protuberance on the surface (no matter if the surface is horizontal or vertical). One can feel it with one’s hands. Segal’s sculptures are extremely tactile. Even the surface of her material is always uneven, as rough as a calloused hand or a brick wall. This amplifies the already enormous internal pressure that form imparts on the material surface. It’s as if the molecular bonds are about to break apart, releasing that pressure and leaving matter behind, like old skin. Sensing this tension, Segal begins to make cuts in her reliefs, cutting out windows and doors. One could say that she creates light inside them. The relief acquires volume, and with it a new space is born.

Thus come to life the recollected worlds of Julia Segal. They are always small-scale, as if we grew up, and they’ve stayed the same. That is why you can peek inside, take them with your hands, put them on the table. Every piece by Segal is a thing in itself, or more precisely, the Object. Jean Baudrillard wrote, “The object is that through which we mourn for ourselves, in the sense that, in so far as we truly possess it, the object stands for our own death, symbolically transcended... “ Julia Segal creates metonymic portraits. Objects instead of people — an old coat, a wheelchair, a child’s table. But her objects are not anthropomorphic (or, more precisely, they are anthropomorphic to the extent that that an old object repeats the figure of its owner).

Segal recreates in detail the real things, as if reclaiming them back from time itself. However, these objects are someone else’s. And if one’s own object allows for at least a symbolic transcendance of death, then someone else’s, on the contrary, painfully highlights

its presence. Thus the artist reveals the emptiness that is formed in space and time with the departure

of each person. And this emptiness resounds with a “voice of gentle silence*.”

Haim Sokol

From the interview with Julia Segal

Interviewed by Michael Polsky

Interviewed by Michael Polsky

|

MP: Were there any artists in your family?

JS: No, my father was a lawyer, and my mother a chemist. The rest of my relatives worked with various technologies. MP: Have you studied drawing as a child? May be in an after-school program or an art studio? JS: No, there was no studio. I did attend a construction college in Alma-Ata, after our family had evacuated from Kharkov to Kazakhstan in 1941. MP: And later you studied at the Surikov Art Institute in Moscow? JS: Yes. And before that I’ve spent two years studying art in Kharkov, then taught at a public school, worked in a puppet theater and television. So I was accepted at Surikov late, at 27. MP: And who were your teachers? JS: First of all, Isaac Itkind, a sculptor. He was exiled to Kazakhstan as a result of the 1937 political repressions. His creative process was very personal; so, it was impossible to study sculpture with him directly. But while spending time with him, I’ve learned something that was more important. You know, in the Jewish tradition, there is an expression: “to pour water on the hands of the righteous man,” and the word “righteous” means roughly the same as the word “holy” in the Russian language. When one not simply listened to the words of an elder, but witnessed him in his daily life — seeing what others usually do not see — this is a rare good fortune. And that’s just how lucky I was: for three years, from the time I was twenty and until I was twenty five, I’ve often spent time in his studio — a small shed, cobbled together from pieces of sheet metal, plywood, and other trash. I do not remember much of what I did there, but I did get to “pour water on his hands”, that’s for sure. Without noticing it, I learned perhaps some of the most important things — how to relate to one’s tools, materials, colleagues, praise, criticism, food, to what happens to your work after its finished — whether it will survive or be completely lost, to one’s financial situation... In short, I was learning what is and what isn’t really important in life. MP: Could you give an example? JS.: If he completed a sculpture in wood, and no one bought it, and there was no one to give it away to, he would throw it out into the snow under his window the very next day to make space for a new piece. There were always five or six pieces lying about, cracking and turning black, as he contentedly worked on a new one. When after a couple of years some museum representatives showed up and bought every one of his pieces, he only shrugged his shoulders: “crazy people”. He accepted pennilessness like bad weather — so there’s rain and snow, and you cant leave your house — so what? He would eat swill made out of watered down canned fish and was happy. I’ve never seen him irritated. If he had a chisel, a hammer and a piece of wood, he’d sing as he worked, quietly glowing with joy. MP: And did you learn to live that way? JS: Such life is unattainable for a regular person, but the ideal remained, and that is already quite a lot. MP: And who were your teachers in college? JS: In Surikovsky we were taught by the masters of Soviet sculpture — Lev Kerbel, Michail Baburin. But in my opinion, we mostly learned from one another, going around the studios of senior students. There we had our own stars. MP: And was there such a figure for you? JS: Yes, you could say that. I was then very interested in the work of Anatoly Masharov, now a well-known Moscow sculptor. What especially fascinated me was that in his work time seemed to acquire physical density. Compared to his sculptures, those of all others seemed transient. Incidentally, it was he who, without knowing it, showed me the path I followed for the rest of my life. Once in the studio, he pointed to the wall with a small window, a radiator and a coil of wire, hanging on a nail, and said, “look — a finished sculptural relief.” And it was like, the scales fell from my eyes, I just started to see. Here is a bicycle leaning against the wall; its a relief. Here is a street, a sign, a lamppost, a park bench, a room with a couch and a television set — all sculpture. And that what I’ve been doing all my life with varied degrees of success. My favorite poet, Bella Akhmadulina, wrote the following lines: “Assured that I already love it/ the object’s voice is droning and begging/It’s soul desires to be praised/and necessarily in my voice...” Professionally, I have greatly benefitted from a friendship with another Moscow sculptor, Marat Babin. He was not as much a teacher, as a critic. He had a kind of an X-Ray vision, when it came to sculpture. When Marat examined your piece, it was as if he was reading every thought that flashed in your mind semi consciously while you were working. In his expression he was always very concise, uncompromising, and eloquent. I’ve always valued his opinion more than that of any art committee. MP: Have you ever wanted to find a group of like-minded people to join? JS: You know, no one was asking me to join a group, and I think that was for the best. Any group thinks of itself as being an elite, and it often is — like professional thieves amidst the amateur criminals. Strangers are not allowed in its circle. I think a group can be great for commercial reasons. Lianozov group, for instance or the “Mit’ki” — is a form of advertising, a brand, as they say nowadays. But the individual inside a group is always, or almost always, a victim: you have to march in step. MP: But you have met other artists that are close to you in spirit? JS: One such artist is Kirill Rozhdestvensky, my daughter’s father. This is so to such an extent that Marat Babin insisted we should do a show together. He used to say: between the two of you, its hard to distinguish where the photograph ends and a relief begins. But Kirill has flatly refused to exhibit in Moscow and in Russia in general. His works were too nonconformist by that time’s standards. And when they made their way to the west, in United States his photographs found their place in various serious collections, including Museum of Modern art in New York. Other works I feel close to are those by a young Israeli artist, now working in Moscow, Haim Sokol. I am very happy about his success and believe in him very much. It was an unexpected present for me to discover the art of a wonderful Hungarian sculptor, Erzsebet Schaar. I feel there is a real connection in our work, but while my pieces are deeply immersed in the details of real life, hers break away from the mundane, and (her best ones) become pure poetry. Too bad this discovery came quite late; had I found her work earlier, perhaps I would have been more audacious with mine. There was also a surprising coincidence. I’ve been told on several occasions that my work resembles that of an American sculptor, George Segal. And when I finally got to see some books about him I noticed that we really did have many themes in common. We are very different artists, of course, both in style and in scale, but when I saw photographs of his “Man in a phone booth”, I didn’t know whether to laugh or to cry: this has been an unfulfilled dream of mine for years. I’ve always loved plaster as a medium and transferred works into bronze only at galleries’ request. I always wanted to create a life-size fragile plaster figure inside a rough metal phone booth. In Moscow at the time it was technically impossible, and that’s too bad... MP: What are your favourites in the history of world art? JS: I love great many things. El Greco’s portraits, Fayum, Giacometti’s drawings, Van Gogh (everything!). I have my favourites among the old Chinese sculpture, as well as African, Mexican and Egyptian sculpture. Recently I fell in love with the XVI century Japanese artist Tohaku, a fabulous master of traditional technique. By the end of his life, he “fell into unprecedented simplicity, as if into heresy”. His last screens seem not to have been painted but “exhaled” onto the canvas with such tenderness, which I’ve seen only in the scene of Eternity in Norshtein’s “ Tale of Tales.” MP: How do you feel in Israel, what kind of influence did the change of your environment have on you? JS: Well, by now the environment in Russia, particularly in Moscow, is also drastically different from that of the 70’s and 80’s, when I’ve lived and worked there. And here? What can I say? You know, there is an episode in the Bible when a prophet asks a woman, wishing to thank her for her help: “Now what can be done for you? Can I speak on your behalf to the king ?” And she answers, so simply: “In the midst of my people I dwell”. |

|

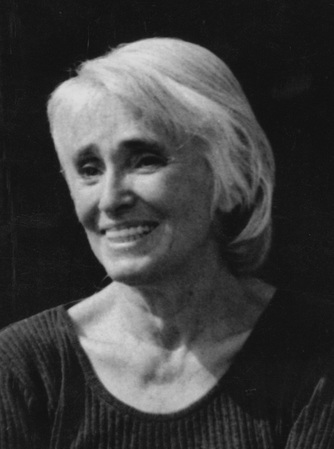

Born July 12, 1938, in Kharkov (Ukraine)

In 1941 the family was evacuated to Aktyubinsk, Kazakhstan In 1948 the family moved to Alma-Ata 1953-57 — Attended Alma-Ata Construction College 1958 — Accepted to the fourth year of Kharkov Art college (sculpture department), after graduation in 1960 came back to Alma-Ata, worked as a school teacher of drawing, an artist in the Alma-Ata puppet theater and later on television studios in Petropavlovsk and Balkhash 1965-71 — Study at the Surikov Art Institute in Moscow 1973 — Membership in the The USSR Artist Union 1978 — Participated in the making of the film “Poor Liza” as a sculptor 1978-87 — Presented regularly at various exhibitions of Moscow artists 1987 — Solo exhibition — Exhibition Hall, 65 Vavilov st., Moscow 1989 — Sculpture symposium in the city of Iserlohn, Germany 1991 — Solo exhibition — Georgi Gallery, Berkeley, CA 1991 — International Artist Conference, San Francisco, CA 1991-93 — Created and ran “Functional Sculpture” company. VDNH Award for the best playground installations in Russia 1994 — Immigrated to Israel 1994-2005 — Lived and worked in artist village of Sa-Nur in Samaria 2002 — Solo exhibition —American Cultural Center, Jerusalem, Israel 2003-2005 — Directed the art gallery of Sa-Nur 2006 — Received the “Olive of Jerusalem” Award 2012 — Creation of the memorial to the artist Mordechai Lipkin and all victims of terror, Jerusalem 2016 — Exhibition at Ilana Goor Museum, Tel Aviv |